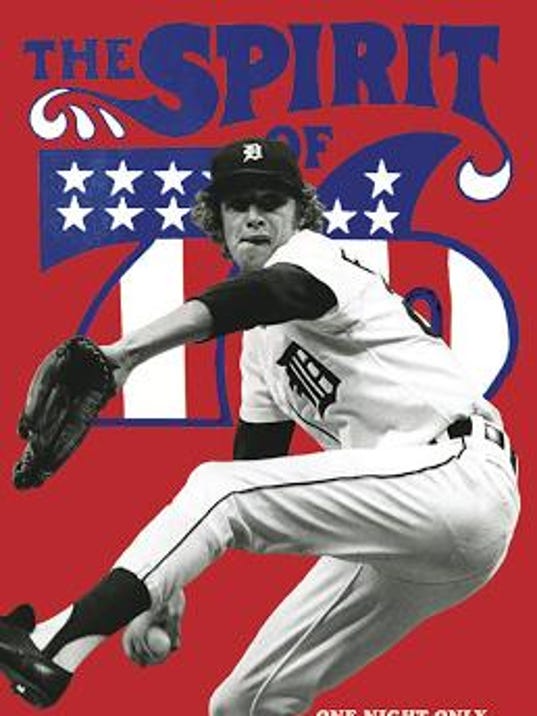

Chris Stevens: 'The Bird' was the word 40 years ago

Tuesday, July 12, 2016 at 8:54PM

Tuesday, July 12, 2016 at 8:54PM If you’re a long-time Detroit Tigers’ baseball fan, you can look back on great summers of baseball and have a really good argument about what was the greatest summer of all.

Was it 1968?

How about 1984?

Recent years have been pretty good, too, with two trips to the World Series, and a number of playoff appearances.

But for me — and many fans in my generation — nothing compares to the summer of 1976. That was a magical experience.

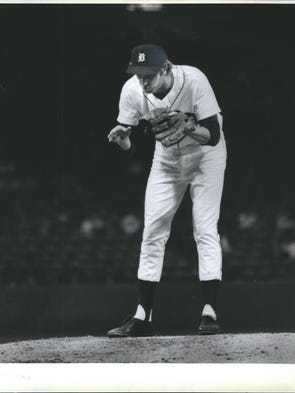

A goofy, curly-haired rookie by the name of Mark “the Bird” Fidrych captivated the sports world with his electric right arm, along with an engaging, refreshing and bubbly personality.

He was not just likeable, he was lovable. When is the last time you’ve heard that said about a professional athlete?

Fidrych took baseball by storm 40 years ago. He made his debut on April 20, and only pitched one inning through mid-May.

Then, on May 15, his world changed, and so did the world of Tigers’ fans.

Fidyrch made his professional debut against the Cleveland Indians and pitched six innings of no-hit ball en route to a 2-1 victory.

From mid-May to early July, Fidrych won seven decisions in a row en route to raising his record to 9-1.

Fans were mesmerized by his talent and on-field antics.

The Bird talked to the ball.

He groomed the mound with his bare hands.

He bounced around the mound like a cocker spaniel puppy.

He smiled, he took curtain calls, he received standing ovations. Oh, and he was a dominant pitcher.

Tiger Stadium would sell out for his starts. Keep in mind, just the year before, in 1975, the Tigers had lost 102 games. In 1976, the Tigers finished at 74-87, 24 games behind the first-place New York Yankees. But the team’s record was pretty much irrelevant. The Bird was the word all summer long.

Fidrych was on the cover of Sports Illustrated and Rolling Stone. He was a celebrity, an athlete, much loved, and created a national buzz that few athletes have ever experienced.

I was in attendance for his 15th win against the Chicago White Sox. He pitched all nine innings, allowed five hits, and the Tigers won 3-1.

For years, I saved the ticket stub to that game. My brother Rick and I stayed for his curtain call. I felt like I was part of history, a witness to something incredibly special.

I had goose-bumps just being there. I was 15 years old, and the Bird was my idol, and the idol of thousands of boys who played baseball.

I still recall the night that he pitched against the New York Yankees on national television. It was ABC’s prime time game (this was several years before ESPN and the ensuing boom of sports on cable television), and the Bird was at his dazzling best in this late-June contest against those dreaded Yankees.

“He’s giving me duck bumps and I’ve watched over 8,000 ballgames!” broadcaster Bob Prince said.

Fidrych won the game 5-1. It took only 1 hour and 51 minutes. Afterwards in his interview with Bob Uecker, Fidyrch was bursting with excitement. Nothing forced. All natural. Genuine.

ABC announcer Warner Wolf stated: “Young Mark Fidrych, thanking his teammates! Look at that, he’s thanking his teammates! He’s thanking the umpires ... everybody ... the grounds crew!”

Minutes after the game ended, probably around 10 at night, one of my neighbors, Marty Ranville, from down the street walked to our house because he knew we’d still be up. He wanted to talk about the game. He was so pumped up about what he saw on TV. And so was I.

I don’t know if I slept that night. It was a rush, just like the entire summer was when he pitched.

Fidrych led the major leagues with a 2.34 ERA, won the AL Rookie of the Year award, and finished with a 19–9 record. He was the starting pitcher in the All-Star Game, but, sadly, injuries piled up and his major league career ended after just five seasons.

As a sportswriter, one of my career highlights was interviewing Fidrych at the Midland Mall. This was probably 15 years ago, and we sat at a table in the back of the old Sears store as autograph-seekers stopped by.

Me sitting next to the Bird, and talking baseball. I never would have dreamt that in 1976.

Forty years ago, Fidrych, who died in 2009 at the age of 54, was the brightest star in the game, and possibly the brightest star in all of sports.

He was Elvis Presley for one summer. He shook up the baseball world.

I remember it. I lived it. I was there.

Simply put, it was the best summer ever for a Detroit Tigers’ baseball fan.

Chris Stevens is sports editor of the Daily News. Email him atstevens@mdn.net

Originally published in the Midland Daily News